Tournament

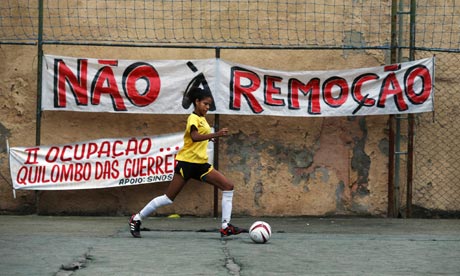

aims to showcase the concerns of locals who say they are being forced from

their homes to make way for World Cup stadiums and Olympic developments Action

from the People’s Cup in Rio de Janeiro. The banners read ‘No to evictions’ and

‘Second occupation, Quilombo of the Warriors’. A quilombo refers to a community

of runaway slaves. Photograph: Pilar Olivares/Reuters

Physically, it’s only a few kilometres away from the Maracanã stadium, but

in symbolism, the People’s Cup could not be much further removed from the mega

sporting events now being staged in Rio de Janeiro and other Brazilian cities.

Instead of the World Cup success story of new stadiums, corporate sponsors

and wealthy football stars, it is a protest event staged in a run-down

community centre, backed by civil rights groups and played out by those who

feel the 2014 finals and 2016 Olympics are being used to push them further down

the social lower divisions.

The event was a foretaste of the widespread protests that have hit Brazil. On Monday, more than

100,000 people took to the streets across the

country to protest against the high costs of the World Cup and poor public

services.

The People’s Cup brings together teams from communities that are threatened

with relocation by the sporting, transport and housing developments that are

now under way in preparation for the upcoming sporting events.

Their banners are tied to the netting around the small, ripped-up,

artificial pitch – Vila Autódromo FC, SOS Providência, Comunidade Indiana

Tijuca and others representing the estimated 29,000 people who are at risk of

losing their homes.

“This is football as a form of protest. We want to remind people that

the authorities are using the World Cup and the Olympics to make illegal

changes to the city,” says Mario Capagnani, who is among the organisers

from the Comite Popular Copa e Olimpíados.

The mini-tournament between 10 male and four female teams is timed to

coincide with the Confederations Cup, which brings

together the continental football champions. The first match

of this World Cup test event took place

on Saturday at a stadium in Brasilia that cost 1bn reals (£320m).

It is one of 12 venues that have either been built from scratch or lavishly

renovated for next year. The government says it wants to use these facilities and

the associated improvements of transport, communications and other

infrastructure to boost development.

Rio, which will also host the Olympics, has some of the most ambitious

plans, including four rapid bus lines, a subway extension, four new highways, the

creation of a huge green space at Park Madeira, and new “smart city”

command and control centres for the police and other social services.

It has refurbished the Maracanã

stadium at a cost of 1bn

reals and is now building projects for the Olympics, including an athletes

village, Brazil’s first public golf course and arenas for handball and rugby.

Bigger still is development of the long neglected port area, which will be used

in the short term for some Olympic media facilities and accommodation, but is

later planned as the home of a dynamic commercial centre including two to five

Trump Towers.

Few doubt that the upgrades are necessary, but civil rights groups question

whether the money has been used as well as it should be and whether the rights

of long-term residents and poor communities are being adequately addressed.

Among the most contentious issues is that surrounding Vila Autódromo, a poor

community in the west of the city that is close to the site of the Olympic

village. The government has said the residents must move because they are

inside what will become the security perimeter. Locals contest this and believe

they are being pushed out because the Olympic village will later become an

up-market residential compound.

“The Olympics only last 27 days so this is really all about real

estate speculation not sport,” says Altair Antunes Cumarães, head of the

residents’ group. “The big construction companies are behind it … For 20

years, they have been trying to move us because there is no more space in the

South Zone for the upper middle class so they are looking here.”

Antunes, a construction worker who formerly lived in the City of God on Rio’s outskirts, says the government has offered his family a new home,

but it is less than a 10th of the size of his current house.

The government says its offer is better than this and that the alternative

homes will be in modern social housing with better facilities. But many locals

say the new places are smaller and far away, which means their communities will

be broken up, and they will have no help restarting businesses or finding work.

The organisers of the football protest claim some people in other areas,

such as Largo do Tanque, have been given just a month to move and paid only

30,000 reals compensation.

Near the huge port area, they say many run-down, empty buildings have been

commandeered for years by housing movements to provide shelter to poor and

homeless people. These groups will be relocated.

In nearby

Providência, many people are being moved for the construction of a cable car and on

the grounds of geological instability (landslides are a deadly problem for many Rio hillsidefavelas). But in this case too, civil rights groups suspect the government is

relocating more people than necessary so it can clear the centre of the city

for business and higher-value residences.

The municipal government disputes this. It says there are no forced

evictions and that development is aimed at improving run-down areas and

providing better transport and other services for poor communities. The World

Cup and Olympics, it says, will accelerate the shift towards a safer and more

modern Rio.

But Witness, a civil rights

group, says 170,000 Brazilians are at risk of losing – or have already lost –

their homes in forced evictions tied to preparations for the World Cup and

Olympics. It says the phenomenon is not limited to Brazil or to major sporting

events: an estimated 15 million people globally are forcibly uprooted from

their homes each year.

Rio wants to demonstrate that it is a modern and tolerant society. But the

debate is far from over, nor is the contest to find meaning in the mega-events

that are reshaping the city.

“We want to show how people are being

threatened. The World Cup is not just a happy get-together. Many people are at

risk of losing their homes,” says Giselle Tanaka, a urban planner and

activist. “But this is also about having fun. Football is not just about

commercial opportunities and sales of brands. Here we show the pure pleasure of

sport.”