Activists protest against gender

violence outside Mexico’s General Prosecutor’s office

in Mexico City on July 11, 2017.Pedro Pardo/AFP

In Argentina, “a woman is killed every 30 hours”, reports Telam, the country’s official news

agency, based on a report of the Observatorio de Femicidios Marisel Zambrano

from the NGO La Casa del Encuentro.

From July 1, 2015 to May 31, 2016, 275 women had been killed.

The violence that takes place in cities goes beyond robbery and assault, the

gang that controls the corner, the abuses, the drug ring that terrorises the

neighbourhood or the illegitimate use of force by diverse actors.

Violence is also hunger, a lack of basic services, and an unjust

legal system. And it is discrimination based on ethnicity, birthplace, sexual

orientation and age.

Urban design is for white young productive men

Women are the omitted subjects in much urban design and

planning. As Saskia Sassen expressed in a 2016 article:

“Urban planning is not gender neutral. While

there has long been research on how urban systems fail to respond to women’s

needs, it was only a decade ago that the subject surged. Since then, countless

cities have been host to initiatives addressing a version of the

‘urban-planning gendergap’.”

Much research and theory is now focusing on gender and cities,

bringing light to these omissions and to the subordinate situations of women in

cities.

Gender is here used as an analytical

category useful for highlighting the asymmetries between men

and women. Society is not binary therefore it is equally concerns LGTBI

population, youth, ethnicities, others.

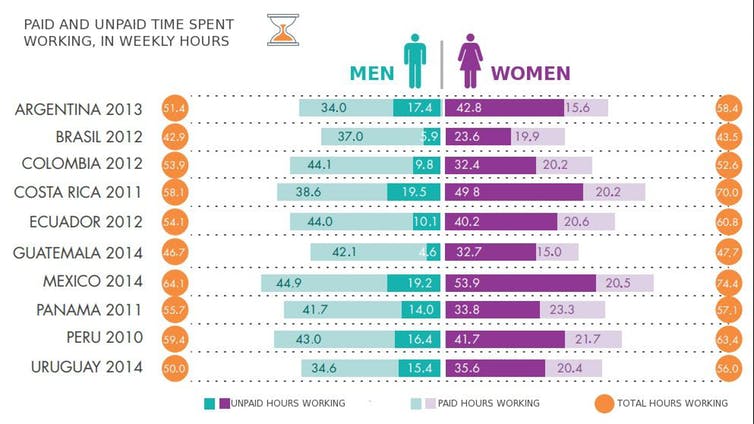

Even as change is happening, many women experience the city

differently than men. Women combine productive work with family duties,

fragmenting the use of time and space. During daylight hours, public spaces are

more likely to be used by women, spending time in nearby parks, with children,

disabled and/or senior citizens. And yet, those spaces are mainly designed for

men’s needs. Urban design and planning, particularly since Modernism, has answered to

a universal citizen: white young productive men.

Millions of women and girls experience violence as a kind of

pandemic, natural, invisible and justified. Only recently has it been seen as

resulting from patriarchal conditions where ideology and culture hide symbolic

dominance and economic exploitation.

Urban planning often does not include women in the design.

Street lights, infrastructures are missing. Unsplash, CC BY-NC-ND

A simple street light can reduce violence

This recognition has produced diverse initiatives. For instance,

the Safe Cities for Women Campaign developed

in Brazil by Action Aid for the municipality of Garanhuns, located in the state

of Pernambuco, launched a plan of public policies for women’s safety.

It includes strengthening the focus on women in special courts

of justice, police stations, police training, improvement in public transport,

investment in street lights, training on gender and violence against women in

schools, and more. Renata, a transsexual woman, political leader in Garanhuns

and an active member of the Women’s Forum of Pernambuco, reports on the positive actions taken by

the city, including how a simple investment in street lighting is reducing

violence.

Denying women’s work

If our understanding of cities and potential policy reforms are

to enhance social progress, we must revisit urban planning from a gender-based

perspective. The use of time and space should be central to gendered planning.

Mothers use time in fragments– domestic

tasks, school and health care each gets its own slice of time.

Women’s responsibilities as family careers are not recognized at

the workplace and thereby their economic contribution to both reproductive and

productive work is rendered invisible. Ana Falú takes this analysis further by

underlining the significance of both kinds of omission: it is the central

factor organizing urban space in ways that build obstacles for women.

As social sciences professor Silvia Federici points out:

“We must admit that capital has been very

successful in hiding our work. It has created a true masterpiece at the expense

of women. By denying housework a wage and transforming it into an act of love,

capital has killed many birds with one stone.”

Figure 5.8: Total time spent on paid and non-paid

work, disaggregated by sex,

hours per week.ECLAC (2016),Author

provided

This is not new. Jane Jacobs taught us in 1961 about the significance

of the proximity of basic services and infrastructures for women in particular.

Gaps in knowledge about omitted subjects are part

of a larger epistemological question central to systemic inequality and its

reproduction. Debates surrounding compact versus diffused cities, or the impact

of new, urban spatial fragmentation must address specific identity-based

exclusions.

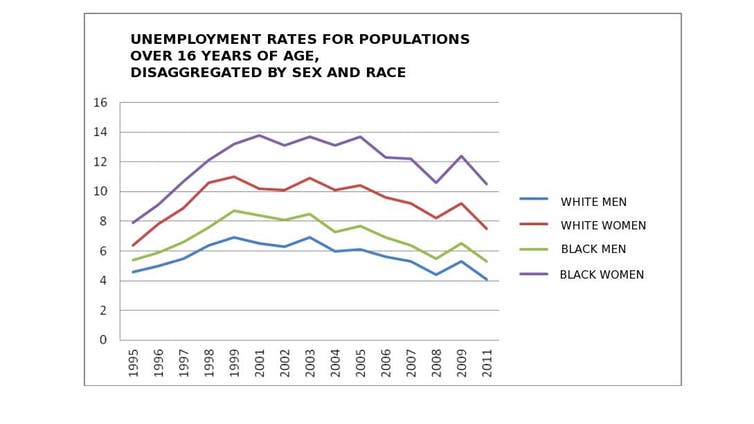

Growth trends tend to be associated with women’s

social progress. And yet even though women at all levels of education are

better qualified than men, they earn less and much search longer for work. The

majority of women work in the low-end service sector.

Unemployment

rate, disaggregated by sex and race.

Based on IBGV/PNAD (2013), Author provided

Assessing the informal sector

A paradox persists: The more women work, the poorer they are.

For instance, in the Latin America and the Caribbean region, female

participation in the work force increased by 21% between 2002 and 2012,

totalling over 100 million women.

In this period, the region registered significant economic

growth and a decrease in poverty, but not among women. In 2002, there were 109

poor women for every 100 poor men; in 2012 the ratio rose to 118.

These trends point to a disjuncture between economic growth and overall social progress, a

pattern not unique to this region. Women constitute the majority of the low-paid service sector.

Haitian

domestic worker, 2012. Women account for the majority of such workers

yet they remain invisible. Alex Proimos/Flickr, CC BY-SA

And in Latin America, 71% of domestic workers are women, most of

whom are indigenous and/or black. Further, poor women have high fertility

rates, having twice as many children than rich women. Accessing sexual, health

and reproductive rights is severely limited due to low social and economic

status.

The patterns in Latin America are evident throughout the world.

Data on the informal sector in India shows that home-based workers, numbering

23.5 million, are mostly women. In the South Asian context, women’s work place is

often determined by social and cultural constraints on mobility. As a result, home-based work is the one or only

possible option for women to secure an income. As in Latin America, this

pattern is unlikely to change even in times of robust development, such as

India saw over the past two decades.

Taking risks to build citizenship

In addition to space and income considerations for social

progress, it is central to consider the intangible dimension of violence

suffered by women in private and public spaces, just because they are women.

The persistence of male violence on the bodies of women to discipline them, is

one of the most universal human-rights violations in the world.

Diverse instruments have been adopted across the world: laws,

protocols, participatory planning and gender budgeting. But progress is slow,

as with all policy, political will and adequate resourcing are key to achieve

impact.

Reports on violence in cities find reports that 60% of women

feel unsafe in urban spaces. Criminality and threats limit women´s freedom of

movement. Women are poor in rights: political participation, autonomy, equal

access to work, infrastructure, transportation and security all are marked by

limited recognition of women’s rights.

Women can become invisible subjects in a context where the city

is a political territory for making citizenship. That is why women often have

to build their citizenship by taking risks. While this risk-taking builds

confidence in terms of advocacy, it nonetheless requires significant economic,

cultural and symbolic resources.

This post

belongs to a series of contributions coming from the International Panel on

Social Progress, a global academic initiative of more than 300

scholars from all social sciences and the humanities who prepare a report on

the perspectives for social progress in the 21st Century. In partnership with

The Conversation, the posts offer a glimpse of the contents of the report and

of the authors’ research.