BRITAIN’S housing market is like food in a

microwave, says Spencer Dale, the chief economist at the Bank of England. It

can “turn from lukewarm to scalding hot in a matter of a few economic seconds”.

Since the crisis the bank has gained new tools to control the market’s

temperature. Now that the heat is rising, it may soon start testing them out.

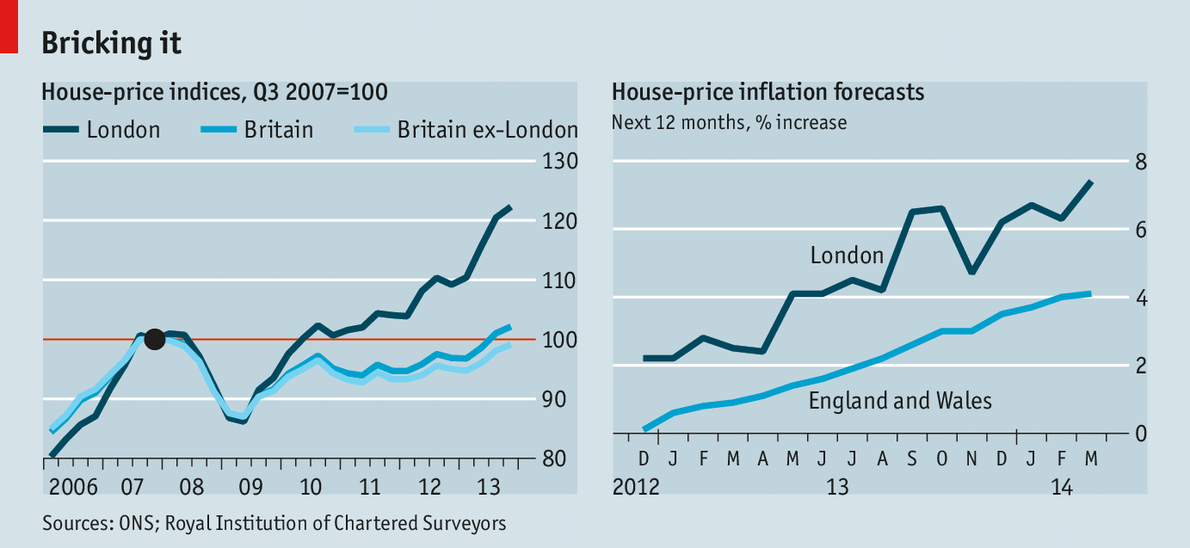

Until last year house prices were rising

predominantly in prosperous central London boroughs. That was largely because

of an influx of cash-rich buyers, says Neal Hudson of Savills, an estate

agency. People saw posh property in the capital as a shelter from economic

turmoil abroad. Elsewhere in Britain, the housing market was torpid. Potential

buyers struggled to find mortgages. Falling real wages, economic uncertainty

and the memory of plummeting house prices during the crisis curbed Britons’

obsession with property.

That changed in 2013. Prices rose by 6.8% in the

year to January, according to the Office for National Statistics (see first

chart). They are still increasing fastest in London—up 13.2% compared with last

year—but the inflation has spread to outer boroughs. In Brent, an unfashionable

part of north-west London, prices have risen 31% in a year, according to a

report from Nationwide, a building society. It recorded chunky increases in

every part of Britain.

These higher prices are a problem for first-time

buyers, but they are not yet unsustainable. Nationally, house prices remain 16%

below their pre-crisis peak, adjusted for inflation. Prices are high relative

to wages, but that is not surprising. Successive governments have failed to

free enough land for new housing developments, while doggedly preserving green

belts. Borrowing costs have fallen over recent decades, in part because of a

global glut of savings, making it easier for Britons to sustain large mortgages.

Neither factor is likely to reverse any time soon.

Even so, the housing market is notoriously prone to

bubbles. In January Mark Carney, the bank’s governor, warned MPs of the dangers

of “extrapolative expectations”—people rushing to buy on the assumption that

prices will continue to surge. Hintsof that are visible. People increasingly think

house prices will keep climbing (see second chart). Even though the

government’s “Help to Buy” schemes, which subsidise higher-risk mortgages, are

probably having only a moderate direct impact, publicity surrounding them has

fed a broader conviction that prices can only go up.

Moreover,

as borrowers chase higher prices their finances are becoming stretched. At the

end of 2013, the average new loan for first-time buyers was 3.4 times the

borrower’s income—the highest level on record. Barclays, a bank, currently

offers mortgages as large as 5.5 times the borrower’s income. While interest

rates are low, payments on such large loans are manageable. But when rates eventually

rise, these borrowers could struggle. A wave of mortgage defaults, accompanied

by falling house prices as banks try to sell repossessed houses, could cause

yet another British banking crisis.

The Bank

of England’s new Financial Policy Committee (FPC) says it is watching for

“emerging vulnerabilities” in the market. Formed less than a year ago to

confront threats to financial stability, including bubbles, its range of

“macroprudential” tools aim to influence the behaviour of the financial system.

Whereas politicians hope rising house prices will cheer voters ahead of next

year’s general election, the committee can afford to take a longer view. With

interest rates expected to remain low for a few more years, it is mulling what

to do.

Dabbing

the brakes

One

approach is stricter vetting of borrowers. From April 26th banks will have to

check that applicants have enough spare cash to cope if the Bank of England

raises interest rates as markets expect (to around 3% in 2019). That is still a

remarkably low standard. Future interest rates are uncertain; in past decades

they have frequently exceeded 5%. The FPC has requested the power to impose

tougher interest-rate tests, and will probably have it by the summer. That

would allow it to curb the size of new loans, without increasing costs for

existing borrowers.

An alternative is more vigorous stress tests of

mortgage lenders themselves, using stringent scenarios that assume interest

rates rise sharply while house prices fall. Forcing lenders to hold buffers

large enough to withstand such a shock should deter them from offering the

riskiest kinds of mortgage.

Kevin

Daly, an economist at Goldman Sachs, an investment bank, thinks the FPC will

enforce tougher affordability tests this year, possibly as soon as June. That

would take some heat out of the market. It could also be unpopular. Poorer

people would have to save for longer to buy a house. Wealthy home-owners would

lose the comfort of swiftly rising prices. And George Osborne, the chancellor

of the exchequer, would probably regret the cooling of a pre-election housing

boomlet. But the FPC is independent for a reason. It should not fear to act.

* To read this news from the original source, click here.