With just over one day to go until the 2016 Summer Olympics

kickoff in Rio de Janeiro, the Olympic legacy already falls short of its

initial promises to the city. Rio is still dealing with inadequate and

unfinished infrastructure projects and overinflated costs, on top of the

economic and political instability facing Brazil. These unfilled promises mimic

the disorganization and corruption from the 2014 World Cup in Rio. Both games

brought promises of meaningful transformations for Rio’s citizens, but instead

ended up violating human rights, increasing public debt, and concentrating

expensive infrastructure mostly in developed neighborhoods.

Six million people

live in the city of Rio de Janeiro, and one in four of them are poor residents

living in slums called favelas. In preparing for the World Cup and Olympics,

the city government announced a comprehensive development plan that they called

the social legacy plan. The favelas have long been starved of investment in

public infrastructure, so the prospect of new developments and upgrades was

exciting. Instead, the plan only further segregated poor residents. In

Providencia, Rio’s oldest slum, the main project was the construction of a $20

million cable car. While developers promised the cable car would connect

residents to jobs, in reality 30 percent of residents were threatened with

forced evictions to make way for the project. Not only was the community

unaware of the project beforehand, but it also had no input in the draft

planning or approval processes.

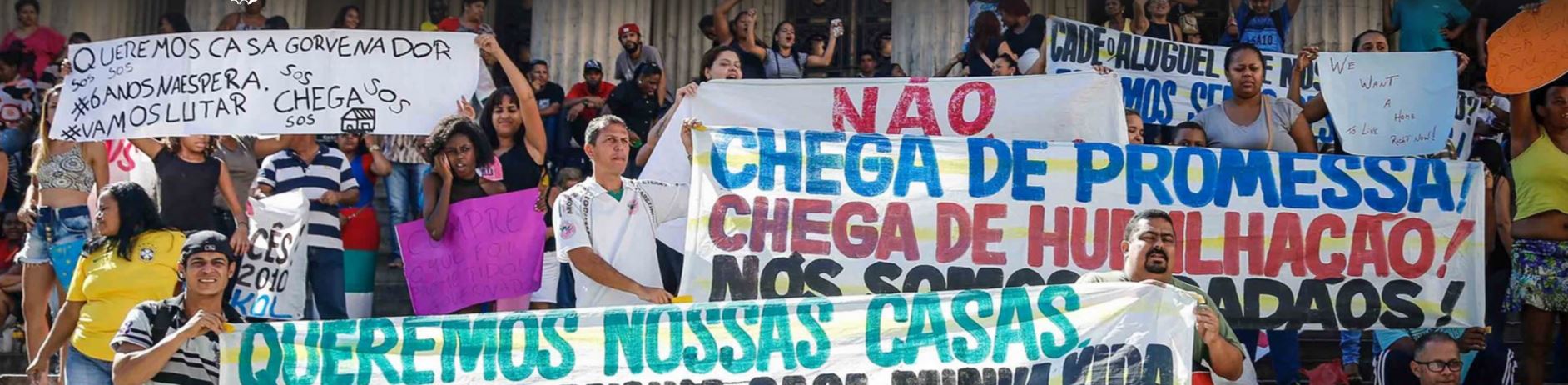

The

damaging effects of the Olympics on Rio’s poor residents

development projects related to major sporting events in Rio have been

controversial. The Popular Committee on the World Cup and the Olympics— a civil

society network comprising social movements, NGOs, research centers and

universities— estimates that from 2009 to 2015, 22,059 families

were forcibly uprooted from

their homes for development projects related to these events. Agencia Publica,

an investigative journalism outlet and a Ford Foundation grantee, told the

stories of 100 evicted families, providing them a voice through one of the

largest multimedia investigations related to the Olympics. According to Agencia

Publica’s co-director Natalia Viana, these firsthand stories provide “concrete

evidence of serious human rights violations, of the right to housing, to

freedom of movement, to information and even freedom of expression.”

Fifty days before the

opening of the Olympics, the governor of Rio declared a state of financial

emergency and asked for federal support to avoid a collapse in public security,

health, education, transportation, and environmental management. The cost of

the Rio Olympics is estimated to be more than $10 billion and that does not

include all of the tax exemptions, public loans, and fiscal incentives that

have not been disclosed. The government gave special legal exemptions to

developers, allowing them to circumvent planning and urban laws, restrict civil

liberties, waive mandatory environmental analyses, ban local and informal

businesses, and criminalize public protests. The NGO Justiça Global, another

Ford partner, produced a video series of

four episodes telling

how such measures are felt disproportionately by those who are already not well

protected, such as those with insecure housing, informal jobs, or already

suffering from marginalization and discrimination.

For example, more than

90 percent of the 900 families living in the low-income community of Vila

Autodromo were forcibly relocated to make way for the Olympic Park, even though

most of them held land concessions titles granted by the state. Although

compensation and nearby alternative housing was offered, many families resisted

leaving, prompting violent clashes with police. The residents felt they were

excluded and disturbed by the games for the capital interests of wealthy

developers.

In reaction to the

negative impacts related to these infrastructure projects, Rio’s government has

responded by blocking access to information and reducing transparency. The

organization Article 19, another Ford grantee, put in 39 Freedom of Information

requests on the impact of the construction of the Transolimpica bus rapid

transit system on the lives of the families whose homes are in the way of the

new bus system. But only one was fully answered. It was impossible to find out

information on the final route of the bus system, although hundreds of families

had already been forcibly displaced.

Additionally, more

than 2,500 people killed by the police in Rio since 2009, as reported by Ford

grantee Amnesty

International. In the month of May alone, 40 people were killed by

police officers on duty in the city and 84 across the state. The communities

most affected by this violence are those living in slums located around the

main access routes to and from the international airport and competition

arenas.

Involving

communities to ensure shared benefits

resulting development and legacy will benefit everyone, wealthy developers are

usually the ones that get all of the gains at the expense of residents,

especially those who are poor and marginalized. So what is

happening in Rio is not a new story.

What is new is that

communities in Rio are starting to push back. A robust civil society network

came together to monitor and collect information on development processes,

expenditures, and rights violations. It helped residents speak out against

harmful development plans and get compensation for those being displaced. The

network submitted reports to international organizations, including the

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and various United Nations

mechanisms. Communities became the defenders of their own rights, and they

sought the assistance of powerful institutions like the Public Defender’s

Office and the UN Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing, leveraging

alternative planning and national and international advocacy.

The alliances

established between communities and relevant stakeholders were unfortunately

not enough to reconfigure the existing power relationship between the city

government and the residents. The laws that were passed to relax tender

regulations and urbanistic controls did not ban forced evictions or set

procedural safeguards, and there was no broad public debate over the nature of

improvements needed.

Governments and public

managers still need to learn how a city can stage world events successfully

while also respecting the rights of the communities living in the path of

infrastructure projects. Participatory development and stricter international

regulation is a good place to start. Just like how government and business

elites organize and lobby to host these games, we must help communities

organize and defend their rights to ensure that they are truly benefitting from

the development and investment associated with these games.