Introduction

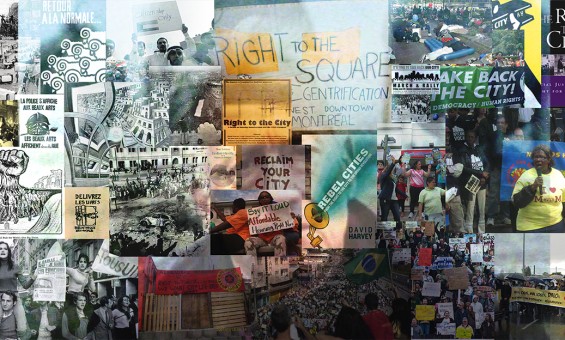

In the last decade,

the right

to the city has evolved as a powerful rallying cry in the call

for social action and struggle against the exclusionary processes of

globalization, a banner which has unified a global struggle to roll back the

commodification and privatization of urban space, and sparked conflicts over

who has claim to the city and what kind of city it should be.

Since riots in

Paris 1968, which adopted the banner of the right to the city based on the work of French sociologist, Henri

Lefebvre, the ideal has inspired a powerful global social movement, fundamental

legislative reform in Latin America, and a myriad of local struggles.

Multilateral agencies and international coalitions are also now exploring the

potential of the right to the city to break the cycle of urban poverty.

Yet despite popular

acclaim, the content of a right to the city remains elusive and its implementation fraught with

challenges. Critical problems of interpretation remain—rights for whom, what

rights and how can they be implemented in apparent opposition to the powerful,

global economic paradigm? The problems of definition and realization are

immense.

This paper

contributes to the debate, focusing first on the genesis of the idea, emerging

themes in academia, and the increasing social exclusion of legitimate social

actors amongst the urban poor, before examining the contribution of global and

local social movements and initiatives to implement the right to the city in national and urban policy. Finally the paper

argues that in the dialectic between social movements, NGOs and the economic

state so far identified, the relationship between urban governments and social

actors is relatively unexplored domain.

Conceptualising the Right to the City

Henri Lefebvre was

perhaps the first to use the term ‘right to the city’. Doyen of the French

Left, Lefebvre’s credentials included his role as a leading philosopher and

activist in the French resistance during World War II. The discussion here

refers mainly to Lefebvre’s 1967 publication Le droit à la ville, and the 1976-78 volumes, De l’état,and then explores three core debates in the

literature—the link between capitalism and urbanization, concepts of

citizenship, and debates on the nature of public space.

Henri Lefebvre and the Paris Left

The outbreak of

violent protests in Paris in the early part of 1968 stemmed student uprisings

in the Sorbonne University and University of Paris at Nanterres (Le Monde

archive, 2010). Heavy police repression sparked national protest and by early

May 1968 unrest had spread to Paris’s Latin Quarter and other cities. On 13 May

1968 unions called a national strike in which an estimated 10 million workers

or almost two thirds of the country’s workforce took part. By the end of May,

President de Gaulle was forced to announce new elections and the strike was

called off.

Henri Lefebvre’s

1967 publication, Le droit à la ville, became something of a cause célèbre for the strikers, creating a radical new paradigm

that challenged the emerging social and political structures of the capitalism.

His analysis revolved round the contradiction between the destruction of the

city and ‘intensification of the urban’ (Mitchell, 2003). He argued that the

traditional city is the focus of social and political life, wealth, knowledge

and arts,an oeuvre in its own right, but the use value of cities as centres of cultural, political and

social life are being undermined by processes of industrialization and

commercialization, creating exchange value and the commodification of urban assets (Lefebvre,

1968: 67 and 101; Lefebvre, 2001; Kofman and Lebas, 1996: 19).

Two central rights

are conferred, the right to participation and to appropriation. Participation allows citizens (urban inhabitants)

to access all decisions that produce urban space (Mitchell, 2003).

Appropriation includes the right to access, occupy and use urban space, and to

create new space that meets people’s needs. Lefebvre argues that:

The right to the city manifests itself as a superior form of rights:

right to freedom, to individualization in socialization, to habit and to

inhabit. The right to the oeuvre,to participation and appropriation (clearly distinct from the right to property), are

implied in the right to the city (Lefebvre

1968 in Kofman and Lebas, 1996: 174).

The right to the city, according to Lefebvre, enfranchises all citizens to participate in the use and production

of all urban space; control over the production of urban space means control

over urban social and spatial relations, thus the social value of urban space

weighs equally with its monetary value. When economic systems value urban space

mainly for its exchange value, Lefebvre argues, the ‘city as oeuvre’ is

suppressed (Purcell, 2003).

The state, Lefebvre

theorized, had entered a new ‘state mode of production’, playing a central role

in the development and legal regulation of ‘capitalist spaces’—be it ports,

housing or infrastructure. Brenner (2001) argues that in recent years states

have acquired ‘unprecedented supremacy’ in urban development because of the

resources they command, resulting in massive deepening of geographical

inequalities as nations, regions and cities become ‘globally competitive

development areas’.

Inspiring though

Lefebvre’s ideas are, many unanswered questions remain. There is little

guidance on how the right to the city might be implemented, how the notion of citizenship

based on residency could be applied, or how notions of participation and

self-management could operate. There are also unanswered questions about the

nature of governance, in particular the role of local government which has a

crucial and decentralized role in mediating local power relations.

Capitalism – the Parasite

The academic

debates that followed Lefebvre’s work see the right to the city as challenging the nature of capitalism and

globalization—whereby economic production is run privately for profit under a

freemarket system which encourages cross border flows. For example, David

Harvey sees urbanization as a set of social relationships reflecting prevailing

ideologies of the relationship between society and basic modes of production

(Harvey, 1973: 303-307). He argues that capitalism always produces a surplus

product which has largely been invested in urban property. Thus, cities have

arisen through geographical and social concentrations of a capital surplus

(Harvey, 2003; 2008).

Consensus indicates

that capitalist-based economic growth facilitates poverty reduction, but the

relationship between growth and poverty varies wildly in different economic and

political contexts. The openness to trade inherent in globalization is linked to increased

market volatility, creating unpredictable outcomes for the urban poor and

threatening poverty reduction (Nissanke and Thorbecke, 2006; Harriss-White,

2003; Lyons and Brown 2010).

Marcuse (2009)

identifies specific periods of financial collapse linked to social upheaval

including: the civil rights movements of 1968; the collapse of Eastern Europe

and the Soviet Union in the 1990s, and the global economic crisis of 2008-2009,

although recent protest has been subdued with little questioning of the

fundamental system. Kaplinsky (2005: 208-249) agrees that persistent poverty

amongst the dispossessed breeds resentment and underpins religious and other

dissident, while an increasingly educated labour force questions the value of

free trade.

At its core, right to the city challenges the role of urban property as the basis

of capitalism, and lays claim to a completely different kind of city and

society, variously termed ‘democratic’ or ‘just’, implying a fundamental

rethink of freemarket capitalism and rights claimed through struggle (Marcuse,

2009, Mayer, 2009). The collective right of the right to the city may embrace individual rights—such as the right to

shelter, or right to work—but is not defined by these. This new right is

defined through continual struggle which allows a reframing of rights and redefinition

of citizenship.

Citizenship and Whose Right to the City?

A second core

debate is the nature of citizenship and who claims the right to the city.

Lefebvre’s idea is that citizenship pertains to all urban inhabitants, not

confined to national citizenship but held by all who inhabit the city, but

applying this notion poses considerable challenges.

Citizenship is

usually accorded to individuals in relation to a social and spatial entity—a

country or city. Citizenship confers on individuals certain rights and

obligations, including the right to have a voice in the exercise of state power

and obligation to pay taxes and submit to state control (Brownet al,

2010; Purcell, 2003). Parnell and Pietersee (2010) identify four tiers of

rights: individual rights of voting, freedom and health etc; collective rights

to basic services including shelter and water; city-scale entitlements such as

safety and social amenities, and freedom from human-induced threats such as

economic volatility or climate change. As yet only the first two tiers are

widely recognized within current human rights regimes.

Cities have now

become the salient sites for citizenship as governments confront the political

status of non-resident citizens, although urban citizenship does not necessarily

negate national citizenship (Dikeç and Gilbert, 2002). Such new citizenships

‘can only be achieved through sustained political struggle’ (Purcell, 2003).

The right

to the city, Marcuse (2009) argues, is claimed

as both a cry from the oppressed (as a result of race, ethnicity, gender or

lifestyle) and a demand from the alienated (including young people, artists,

and idealists decrying the dominant economic system).

The concept of

residency as a basis for citizenship widens the definition of who has a right to the city. However, it entails major difficulties and omits

key constituencies of the urban poor, such as undocumented migrants and workers

in the informal economy for whom temporary status or insecurity make

enumeration difficult. It also ignores the numerous commuters that swell city

centre populations during the day, but live elsewhere. As Lefebvre argues, to

frame citizenship in formal and territorial terms fails to recognize the city

as a political community, and the social relations of power (Dikeç and Gilbert,

2002; Brown, 2009).

Claiming Rights to Public Space

‘Se Tomaron Las

Calles’, John Friedman wrote after visiting the fiesta of

Santiago and Santa Ana in Tudela, Spain, where the whole population celebrates

– wearing white, waving red banners, and racing round the bandstand (1992). He

suggested that there are only two occasions when people claim the streets, to

protest against an oppressive state, or to celebrate (Friedman, 1992).

Present ideologies

of urban production are based on inalienable rights to property (usually private)

as productive space (Harvey, 2003). Thus public space (as the space for representation) takes on an

exceptional importance, both as the

space for debate

and claim of democratic rights, but also for those excluded from the

commodified private domain (Mitchell, 2003:34, Brown, 2006:18). Public space is

the focus of an inherent and ongoing struggle over rights, as people compete

over the shape of the city, access to the public realm, or rights to

citizenship (Mitchell 2003: 18). Public space thus played a key part in

democratic debate and representation (Low and Smith, 2007: 5; Banerjee, 2001).

Public space is

also the site in which exclusion is played out. Mitchell (2003: 230-232) cites

examples of homeless people in the USA who are moved on from sleeping in public

parks, arguing that criminalization for rough sleeping is a testimony to

unequal power, and that order should be contingent upon social equality.

Cultural mores restrict women’s use of public space (Massey, 1994; McDowell and

Sharp, 1997), and the development of gated communities results in increasing erosion

of the public domain (Webster and Lai, 2003: 5).

Struggles against Exclusion

Since mid-1980s,

the call for the right to the city has crystallised a series of demands as urban

residents struggle against the continued erosion of rights. These have coalesced

around the demands of two broad groups, the deprived seeking access to basic

rights for secure shelter, clean water or dependable livelihoods, and

anti-globalization and global justice movements challenging the dominant

economic system (Marcuse, 2009; Mayer, 2009). In recent years, global and local

social movements, alliances of city governments and multinational

organizations, have adopted the right to the city as a slogan to renegotiate the contract between

state and citizen.

Global Social Movements

At a global level,

one of the most influential social initiatives is the World Charter on the

Right to the City. The world charter sprang from dialogues in the 1990s amongst

human rights activists, environmentalists and others at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit

and the 1996 UNCHS forum in Istanbul, Habitat II. More recently, the charter

was adopted as a theme in the World Social Forum (WSF), the annual meeting of

social movements opposed to neoliberal globalization first held in Porto Alegre

in 2001 in celebration of the city’s experimental forms of local governance.

The world charter

seeks to establish the right to the city as a new human right, to be adopted by the UN and

national and local governments (Saule Junior, 2008). The central conception in

the charter is the definition of collective rights so that:

Article 1: Everyone has a right to the city without

discrimination of gender, age, race, ethnicity, political and religious

orientation and preserving cultural memory….(WSF, 2004)

Citizens are

defined as ‘all people who live in the city, either permanently or in transit’

(WSF, 2004).

The world charter

encapsulates many of the ideas in Lefebvre’s vision, seeing the right to the city as a collective right, and calling for a

recognition of the social function of property. Two key aspects appear

controversial – the inclusive definition of ‘citizen’ regardless of formal

residency status, and establishing the social function of property, so the

charter has not yet been taken forward by the international agencies.

Local Social Movements

Many local social

movements have adopted the rights-based agenda in the struggle for urban

resources with four waves of urban mobilization since the 1960s (Mayer 2009).

In the 1970s, struggles coalesced around housing, rent strikes and protests

again urban renewal; the 1980s saw reactions to austerity policies and

neoliberalism; 1990s protests focussed on government programmes for ‘local

economic development’, and since 2000 a global struggle has emerged against

integration of financial and property markets, and intensifying social

polarization between the ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’.

For example, in

Brazil the increasing politicization of wastepickers led to the creation of

National Waste and Citizenship Forum, as a means to strengthen participatory

approaches to the management of urban waste (Dias 2009). The forum publication

of a UNICEF study which estimated that 45,000 children worked as wastepickers

in Brazil, up to a third without schooling. The forum aimed to eradicate child

labour at open dumps, eliminate unmanaged dumps, and achieve recognition of the

rights of wastepickers as legitimate urban service providers.

Legislative Reform

Some suggest that

the right

to the city can only be addressed through fundamental legal

reform. Most interesting, perhaps is the extraordinary experiment unravelling

in Latin America, where a number of states are enshrining the right to the city in modern legislation, including the approval of Law

10.257/2001 in Brazil, the City Statute.

In Brazil, informal

urban development has become the norm as a result of a speculative land market,

clientalist politics, and an exclusionary legal regime (Fernandes, 2007). The

City Statue was conceived in the mid-1980s during Brazil’s transition from

military to democratic rule. As a result of lobbying from a grouping of civil

society organisations, and establishment of the National Urban Reform Forum,

the new federal constitution of 1988 included two sections on urban issues

(Articles 182 and 183). After many years of struggle by the forum, the articles

were eventually passed into law as the 2001 City Statute (Cities Alliance,

2010).

The City Statute

explicitly recognises the right to the city as a collective right, based on three core

principles:

·

the

concept of the social function of property

·

fair

distribution of the costs and benefits of urbanization, and

·

democratic

management of the city (Rodrigues and Barbosa, 2010).

The law established

a new Ministry for Cities, and a national charter to implement the City Statute

was approved in 2002.

A change in the

political culture of local institutions is critical for realizing the right to the city if a pro-poor rights-based agenda is to be achieved

and by grassroots organisations who must move from opposition to a more

positive role, as Parnell and Pietersee (2010) argue through their study of

Cape Town. Mayer (2009), dismisses the actions of local administrations as

simply reinforcing the status quo, but this paper argues that the power balance

between economic production, civil society and governance mechanisms must be

addressed.

The Multilateral Agenda

Several

international initiatives within global coalitions of local governments and the

multilateral agencies have opened space for debate, many of them drawing on the

framework of the 1948 UN Declaration of Human Rights and subsequent

international human rights instrument. Of note is the European

Charter for the Safeguarding of on Human Rights in the City agreed at 2nd European Conference on Cities for

Human Rights in May 2000 attended by local authorities (IDHC, 2010).

The European

charter addresses the city as a collective space, to ensure rights of all

residents to political, social and ecological development with a commitment to

solidarity; municipal authorities are charged with respect for the dignity and

quality of life for residents. The charter has no legal standing but forms a

political commitment by the 350 city governments who are signatories. Other

international and city charters also seek to strengthen rights and define

responsibilities, such at the Global Charter-Agenda for Human Rights in the City now being developed by United Cities and Local

Governments, the global association of local governments.

Amongst

multinational programmes most directly addressing the right to the city, are the projects by UNESCO and UN-HABITAT. From

2005-2008, a joint project entitled Urban Policies and the Right to the City: Rights,

responsibilities and citizenship, sought to identify good practice in law and urban

planning that strengthen rights and responsibilities, for example promoting

inter-faith tolerance and the participation of women, and a role for young

people and migrants in urban management. From the debates, five common policy

agendas were identified: liberty and freedom in city life for urban residents;

transparency, equity and efficiency of city administrations; participation in

local democratic decision-making; recognition of diversity in

economic,social and cultural life, and reduction poverty, social

exclusion and urban violence (Brown and Kristiansen, 2008).

Discussion

The banner of the right to the city has inspired an extraordinary global protest that

challenges the dominant economic order. This protest is played out by global

social activists, numerous local campaigns, progressive international

associations and governments seeking a fairer contract between state and

citizen. There are, however, countries, cities and contexts which the debate

cannot reach where freedom of speech is inadvisable or the context for social

action is limited.

There are many

critics of multilaterals in their approach to poverty reduction. The

presumption is that benign governments supported by good information can

address critical problems of urban poverty. The approach of often normative,

assuming a common understanding of concepts such as ‘good governance’ and

‘social exclusion’, but with little real critique of the political, economic

and cultural context of urban growth (Jenkins et al,2007: 184).

A more specific

critique of the right to the city agenda is made by Mayer (2009) who suggests that

while institutionalizing rights may go some way to address exclusion, this is

nothing more than a claim to inclusion in the system as it exists which fails

to address the underlying economic processes from which such inequalities

spring. Whilst charters and guidelines may have limited value, they downplay

the core struggle for power at the heart of the right to the city (Mayer, 2009).

Enshrining the right to the city in legislation appears to be a crucial, if

difficult, driver of change. The City Statute in Brazil was the product of a

particular confluence of events, the change to democratic rule and widespread

acceptance of a role for social activisim and coalitions of the urban poor.

Nevertheless, the right to the city has also been adopted elsewhere in Latin America,

in Colombia, Ecuador and Mexico (COHRE Bulletins 2008-2010). How these

initiatives unfold will be crucial in taking forward the fundamental reform

that the right

to the city entails.

Perhaps, most

crucially, the approach presents a key role for the local state in introducing

a rights-based agenda, including the third and fourth tier of rights identified

by Parnell and Pietersee (2010)—rights to city-scale entitlements and freedom

from human-induced threats such as economic volatility or climate change. The

local state, represented by the institutions of city government and other

state-related organizations, has a crucial role in mediating power relations

between citizen and global and local system of production.

The right

to the city is a powerful

banner with broad appeal under which to address injustices of the modern city.

The use of new media in attempts to coopt existing power bases provides scope

for incremental change, which cumulatively will strengthen rights for the urban

poor. However, this paper argues that it is only by readdressing the power

balance in the triangle between economic production, civil society and

governance that real progress can be gained.

REFERENCES

Banerjee, T. (2001)

The future of public space: beyond invented streets and reinvented places,Journal of the American Planning Association, 67(1): 9-24

Brenner, N. (2001)

State theory in the political conjuncture: Henri Lefebvre’s “Comments on a new

state form”,Antipode 33(5): 783-808

Brown, A. (2006),

Contested Space: Street trading, public space and livelihoods in developing

cities,ITDG Publishing: Rugby

Brown, A. (2009)

Rights to the city for street traders and informal workers, in Jouve, B. (ed) Urban Policies and the Right to the City:

UN-HABITAT and UNESCO Joint Project,Collection Citurb, Presses universitaires de Lyon:

Lyon

Brown, A. (2010)

e-Debate 1 Report: Taking forward the right to the city, UN HABITAT

http://www.unhabitat.org/downloads/docs/Dialogue1.pdf, accessed August 2010

Brown, A. and

Kristiansen, A. (2008) Urban Policies and the Right to the City: rights,

responsibilities and citizenship,UNESCO, MOST (Management of Social Transformations)

Programme: Paris, http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0017/001780/178090e.pdf,

accessed August 2010

Brown, A., Lyons,

M. and Dankoco, I. (2010) Street-traders and the emerging spaces for urban

citizenship and voice in African cities,Urban Studies,47(3): 666-687

Cities Alliance

(2010)City

statute of Brazil: a commentary,

Cities Alliance, Brazil Ministry of Cities, National Secretariat for Urban

Programmes: Washington

COHRE (2008-2010)

Bulletin on housing rights and the right to the city in Latin America, 2009

Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE), http://www.cohre.org/bulletin,

accessed August 2010

Dias, S. (2009) Trajetórias e Memórias dos Foruns

Lixo e Cidadania no Brasil:Experimentos Singulares de Justiça Social e

Governança Participativa. PhD Thesis, Belo Horizonte FAFICH/Programa de

Doutorado em Ciência Política da UFMG.

Dikeç, M. and

Gilbert, L.(2002) Right to the city:homage or a new social ethics?,Capitalism Nature Socialism 14(2): 58-74

Fernandes, E.

(2007) Constructing the ‘right to the city’ in Brazil, Social Legal Studies,16(2): 201-219

Friedmann, J.

(1992) The right to the city, Society and Nature: The International Journal of

Political Ecology,1(1): 71-84, Athens, London, Society and Nature

Press

Harriss-White, B.

(2009) Globalization, the financial crisis and petty production in India’s socially

regulated informal economy, Paper to the 11th AHE Conference (Association for

Heterodox Economics), Panel 1: Informal economy and the developing world:

social networks and sustainability, July 2009

Harvey, D. (1973) Social Justice and the City, Edward Arnold Publishers: London

Harvey, D. (2003)

The right to the city, International Journal of Urban and Regional

Research, 27(4): 939-941

Harvey, D. (2008)

The right to the city,New Left Review,53, Sept/Oct: 23-40

IDHC (2010)

European Charter for the Safeguarding of Human Rights in the City, Institut de

Drets Humans de Catalunya (IDHC), http://www.idhc.org/eng/131_ceuropea.asp,

accessed August 2010

Jenkins, P., Smith,

H. And Wang, Y-P. (2007) Planning and Housing in the Rapidly Urbanizing

World, Routledge: London and New York

Kaplinsky, R.

(2005) Globalization,

Poverty and Inequality: Between a rock and a hard place, Cambridge, Polity

Kofman, E. and

Lebas, E. (eds and translators) (1996) Writings on Cities, Blackwell Publishing: Oxford

Le Monde (2010)

France history archive, Paris May 1968, dates and principal events, Metropolis,

http://www.marxists.org/history/france/may-1968/timeline.htm, accessed August

2010

Lefebvre, H. (2001)

Comments on a new state form, Antipode 33(5): 769-782

Lefebvre, H. (1968) Le Droit à la Ville, in Kofman, E. and Lebas, E. (eds and translators)

(1996) Writings

on Cities, Oxford, Blackwell Publishing

Low, S. and Smith,

N. (eds) (2005) The Politics of Public Space, Routledge: New York

Lyons, M. and

Brown, A. (2010) Has mercantilism reduced urban poverty in SSA? Boom and bust

in the markets of Lome and Bamako, World Development,

38(5): 771-782.

Marcuse, P. (2009)

From critical urban theory to the right to the city, City 13(2): 185-197

Massey, D. (ed)

(1994) Space,

Place and Gender, Blackwell Publishers: Oxford

Mayer, M. (2009)

Shifting mottos of urban social movements,City,13(2): 362-374

McDowell, L. and

Sharp, J., eds. (1997) Space, Gender, Knowledge: Feminist readings, Arnold: New York and London

Mitchell, D. (2003) The Right to the City: Social justice and the fight

for public space, Guildford Press: New York

Nissanke, M. and

Thorbecke, E. (2006) Channels and policy debate in the globalization –

inequality – poverty nexus, World Development,34(8): 1338-1360

Parnell, S. and

Pietersee, E. (2010) The ‘right to the city’: institutional imperatives of a

developmental state, International Journal of Urban and Regional

Research,34 (1): 146-162

Purcell, M. (2003)

Citizenship and the right to the global city: reimagining the capitalist world

order,International Journal of Urban and Regional Research,27(3) pp564-590

Rodgrigues, E. and

Barbosa, B.R (2010) Popular movements and the City Statute, in Cities Alliance

(2010)City

statute of Brazil: a commentary,

Cities Alliance, Brazil Ministry of Cities, National Secretariat for Urban

Programmes: Washington

Saule Junior, N.

(2008) The right to the city: strategic response to social exclusion and

spatial segregation, in Institution Pólis,The Challenges of the Democratic Management of

Brazil, Instituto Polis: São Paolo

Webster CJ and Lai

LWC (2003) Property

Rights, Planning and Markets: Managing spontaneous cities,Edward Elgar: Cheltenham UK and Northampton MA, USA

WSF (2004) World

Charter on the Right to the City, World Social Forum (WSF)

http://v1.dpi.org/lang-en/events/details.php?page=124, accessed August 2010